As in the rest of Italy, measures for the protection of monuments from air raids had been taken since the 1930s. These were implemented soon before the beginning of the war.

In Someda de Marco´s journal, this topic, as regards the whole art heritage in Friuli, becomes dominant especially after September 8th, 1943. The escalation of air raids obliged to take major measures for the safety of the more exposed, or fragile, monuments, both in Udine (side door of the Duomo, Manin Chapel, apse of S. Maria di Castello) and Cividale.Activities were carried on despite the difficulties regarding the supply of materials and transport.

As for the protection of frescos, monuments at highrisk were provided with sturdy props and wooden structures, which were applied to the precious surfaces, in order to limit damage from strong airflows. Paper bags filled with wooden shavings were positioned between the frescoed surfaces and the supports, and cardboard panels between the latter and the paintings. This way, a soft protection was created, also adaptable to the various heights of ceilings.

German authorities eased the operations designed and carried on by Italian officers, as was later also attested by the Allied forces in a Report of August 2nd, 1945.

“The creation of protective works to prevent possible damage by air–attack to important monuments was a normal part of the Italian Superintendency´s functions, and the activity of the Abt. Denkmalschutz was in this respect in the main that of smoothing out administrative difficulties and helping in the supply of materials. The only recorded instance of direct action by the Abt. Denkmalschutz was, significantly enough, in the case of a church at TARVISIO, which confirms the view that territory in this valley up to the old Italo–Austrian frontier was in fact considered as effectively part of the Reich.” (London, Public Record Office, WO 204/2992)

Someda de Marco was worried in particular for the frescoes in the Church of Santa Maria del Castello and in the Cappella della Purità, this last decorated by Tiepolo.

As regards the former building, it had sustained damage caused by previous tunnelling through the Castle hill: in September 1944, a sturdy supporting centering is applied to the broken arch, after the crack had gotten worse “despite the reassurences given by engineers”.

A few months later, the restorer Giuseppe Buzzi was given the task to apply protective veils to the frescoed surfaces, where the colour was more fragile. A few days later, however, the solution was deemed not sufficient and the order was given to detach the frescos, which would be stored in the Museum.

In May 1944 proposals about the detaching of Tiepolo´s frescoes in the Cappella della Purità in Udine were discussed, and the following year they were again put forward.

Someda de Marco was absolutely adverse to the idea. He was frightened by the risks that artworks would come across in the case of a faulty operation.

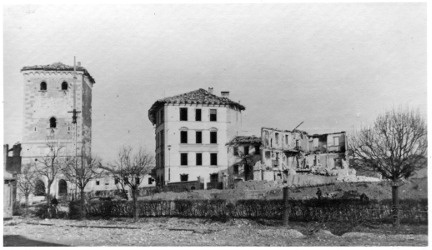

Among the areas under Someda de Marco´s protection, Carnia, in particular, versed in a disastrous situation. During Autumn 1944, “the presence of caucasian troops, that don´t respect, nor spare anything” caused hign concerns.

The transfer of paraments which furnished the small Carnic churches, was taken into account, but soon let aside.

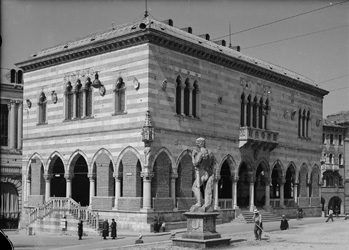

Someda de Marco´s journal is also a meticulous report of the damages suffered by the art heritage during the bombings of Udine.

Damages caused by the bombing in February 1945 were particularly detrimental for the Archivio Notarile of Udine, that lost its most precious section, the one containing documents from 1300 to 1500. Just few days before, Someda had organized the transfer of archival materials to his own home in Ceresetto, to guard them from air raids. Moreso, after bombing documents were not immediately preserved and were let at the mercy of anyone for almost eight days.